O Clima mudou

Mas você, leitor, já está acostumado com isso. A meteorologia é tão complexa quanto a economia, mas isso não implica que os governos e as pessoas caiam no laissez-faire simplesmente porque não podem prever seus rumos. Você faz seguros, faz poupança, se prepara para dias onde o "clima da sua vida" irá mudar. Os governos fazem politicas econômicas, industriais, sociais etc. Mesmo na ausença de consenso. Mesmo quando os cenários não são unânimes entre os economistas. Pois você tem que agir baseado na melhor informação disponível, não na verdade absoluta (coisa que não existe em ciência).

Sem dúvida, um "clima" de alarmismo (desculpem de novo) também pode ser prejudicial, por jogar as pessoas ou no ceticismo ou na resignação sem esperança (as pessoas, especialmente os céticos, passam convenientemente de uma atitude a outra). Por outro lado, a teoria de decisão estatística diz que é melhor acreditar em um falso positivo do que um falso negativo. Este é o dilema, que todos enfrentamos no dia a dia: se alguém grita "FOGO!" no seu prédio, você pega suas coisas e sai correndo ou fica esperando por um consenso científico sobre o tema?

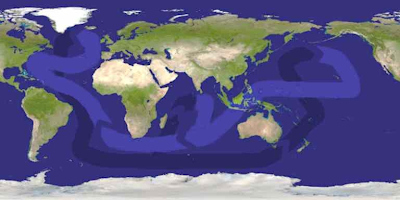

In its most detailed portrait of the effects of climate change driven by human activities, the panel predicted widening droughts in southern Europe and the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, the American Southwest and Mexico, and flooding that could imperil low-lying islands and the crowded river deltas of southern Asia. It stressed that many of the regions facing the greatest risks were among the world’s poorest.

And it said that while limits on smokestack and tailpipe emissions could lower the long-term risks, vulnerable regions must adjust promptly to shifting weather patterns, climatic and coastal hazards, and rising seas.

Without such adaptations, it said, a rise of 3 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century could lead to the inundation of coasts and islands inhabited by hundreds of millions of people. But if steady investments are made in seawalls and other coastal protections, vulnerability could be sharply reduced.

The group, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, also noted that the climate shifts would benefit some regions — leading to more rainfall and longer growing seasons in high latitudes, open Arctic seaways and fewer deaths from the cold.

The 1,572-page report, finished here on Friday, was prepared by more than 200 scientists, and a 21-page summary was endorsed by officials from more than 120 countries, including the United States.

The conclusions came after four days of revisions by scientists and then an often rancorous all-night debate with government officials. In a sign of shifting geopolitics on global warming, scientists who worked on the report criticized China for weakening some language in the summary, while they credited the United States, which had for years stressed uncertainty in the science, with playing a mostly constructive role.

The panel, which has tracked research on global warming since it was created under United Nations auspices in 1988, has sometimes been criticized for allowing governments to shape the summaries of its periodic reviews of climate science.

But by many accounts, it remains the closest thing to a barometer for tracking the level of scientific understanding of the causes and consequences of global warming. In February, the panel released its fourth summary of basic climate science, concluding with 90 percent certainty that humans were the main cause of warming since 1950.

The new report, focusing on the effects of warming, for the first time describes how species, water supplies, ice sheets and regional climate conditions are already responding to the global buildup of heat. While the report said that assessing the causes of regional climate and biological changes was particularly difficult, the authors concluded with “high confidence” — about an 8 in 10 chance — that human-caused warming “over the last three decades has had a discernible influence on many physical and biological systems.”

At a news conference here, Martin Parry, the co-chairman of the team that wrote the new report, said widespread effects were already measurable, with much more to come.

“We’re no longer arm-waving with models,” he said. “This is empirical information on the ground.”

Reports from the panel are released only every half-decade or so, and this year’s suite of three studies — on basic science, the effects of warming, and options for cutting emissions — are likely to guide policymakers for years to come.

Para continuar, clique aqui. Esta postagem pertence à Roda da Ciência. Clique aqui para colocar comentários.

Comentários